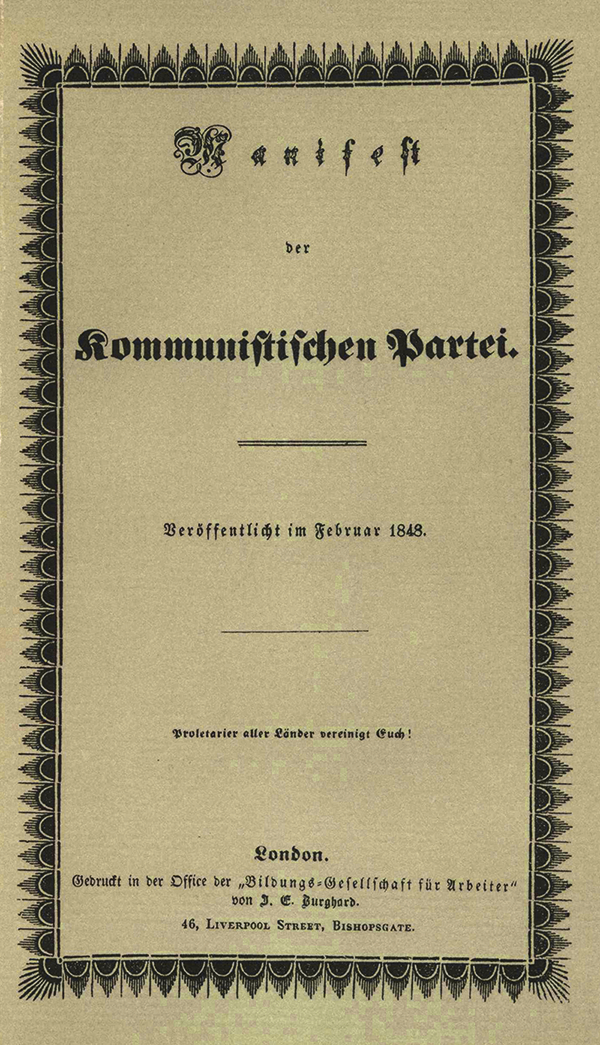

- Socialism and Marxism. I've written two extensive blog posts about Marx and socialism, but I feel I've only scratched the surface. My shallow study has led to me to belive there are so many problems and contradictions in fundamental Marxism, it is a wonder to me that anyone found him an inspiration or built upon his ideas in the first place. Yes, his ideas seem like they could be the start of a utopian society if the government could be trusted to actually get everything right in favor of the people, but as history and revolutions have proven, any government has flaws. Giving a flawed government the powers Marx would seems like a serious mistake, and I feel history has shown us that. Leninism, Stalinism, Maoism, and most communist and socialist governments seem like they have been directly responsible for deaths and horrible lives for thousands if not millions.

Maybe I'm wrong though. Maybe that's a result of a biased capitalist Western view. Or maybe Marx would have denounced everyone of these dictators as imposters, not practicing his ideals at all. That's exactly why this topic is so fascinating to me. I want to do a deeper study of Marxism and identify how supposed Marxist followers differed from or followed Marxist ideals, what went wrong and what went right, and what would have to change in order to create an ideal Marxist society in today's world. And then I'd take all those findings and apply them to a digital world. Is the digital world more like capitalism or Marxism? Which system works better? What evidence is there to back such findings up? As you can see, I could quickly get carried away on this path. I'd have to find a way to trim all that down into a this semester timeline. :)  Comparing historical revolutions to modern revolutions, like the Arab spring. Analyzing crowd dynamics both. We've talked a lot about crowd sourcing and the wisdom of the crowd. How did such principles play into historical revolutions? How did the rebellion of a few turn into a rebellion of the many? Why did it do so? How did rebels act together towards a common goal, and what were the crowd dynamics in the aftermath? How does all that compare to today's revolutions?

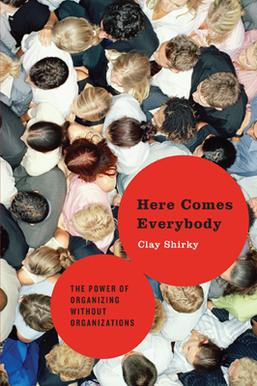

Comparing historical revolutions to modern revolutions, like the Arab spring. Analyzing crowd dynamics both. We've talked a lot about crowd sourcing and the wisdom of the crowd. How did such principles play into historical revolutions? How did the rebellion of a few turn into a rebellion of the many? Why did it do so? How did rebels act together towards a common goal, and what were the crowd dynamics in the aftermath? How does all that compare to today's revolutions? Participation in the modern age. In the past, true participation was somewhat limited. The wealthy had more privilege to communicate. The newspapers and editors became a way to circulate ideas, but only a small percentage of the population actually wrote for newspapers. It evolved to radio, then television, and now the Internet. How many of our population fully participate online? To what extent? Why is that only a smaller percentage of our friends seem to constantly be posting on Facebook instead of everyone? And why the heck do they post what they do? I don't care what they ate for lunch today. What is participation really like now, not just quantity, but quality?

Participation in the modern age. In the past, true participation was somewhat limited. The wealthy had more privilege to communicate. The newspapers and editors became a way to circulate ideas, but only a small percentage of the population actually wrote for newspapers. It evolved to radio, then television, and now the Internet. How many of our population fully participate online? To what extent? Why is that only a smaller percentage of our friends seem to constantly be posting on Facebook instead of everyone? And why the heck do they post what they do? I don't care what they ate for lunch today. What is participation really like now, not just quantity, but quality?

There are so many questions to ask for each of these topics, and the amount of information to consume is overwhelming. These are the three areas that interest me more, but they sound like better topics for graduate research than for a class project for the last half of the semester. Maybe I'll have to give up on these for now, or at least seriously trim down the scope of whichever one I end up doing. Of course, actually getting to use one of these depends on the interests of others. Anyone interested? Anyone? Bueller? Bueller?

;U136658.jpg)