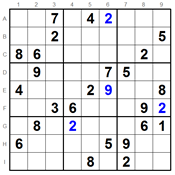

Well, Thursday's exercise in mass Sudoku playing turned out to be an epic fail. I was guilty of eagerly plowing along with several other classmates on a collaborative sudoku puzzle, competing with the sole player who was unlucky enough to be the butt of our competitive egos. We eagerly announced our completion of the puzzle only a few minutes later... and realized it was entirely wrong. Somehow the puzzle had gotten messed up beyond repair, and eventually I and the rest of my classmates abandoned the puzzle.

The activity was meant to be a demonstration of the power of open collaboration. It was class crowd sourcing, and for some reason it didn't work. Why did it fail? We were trying to hard to beat our sole adversary, and we trusted each other too much. It backfired. We didn't reach the solution, we were demotivated, and we never did finish the puzzle.

I have recently been reading the book Wisdom of the Crowds, by James Surowiecki. It's a great book that counters advocates the idea that the wisdom of the group is often as good as if not better than the smartest individual. It seems that our experience in class would counter his argument, but he gave four conditions that characterize wise crowds:

I have recently been reading the book Wisdom of the Crowds, by James Surowiecki. It's a great book that counters advocates the idea that the wisdom of the group is often as good as if not better than the smartest individual. It seems that our experience in class would counter his argument, but he gave four conditions that characterize wise crowds:- Diversity of opinion. Each person should have some private information, even if it's just an eccentric interpretation of the known facts.

- Independence. Each person's opinions are not determined by the opinions of those around them.

- Decentralization. People are able to specialize and draw on local knowledge.

- Aggregation. Some mechanism exists for turning private judgements into a collective decision.

After looking at his points, it is clear that our class did not meet the requirements of a wise crowd, even if we met some of them. We did have diversity of opinion in that each person was working on the puzzle from a different perspective, and were diversified in angle attack. For example, I could be looking to complete the third column while someone else could be working on completing all the 2's. We kind of decentralized in that sense as well, each person working from their own angle. The puzzle itself was an aggregation of sorts, combining all of our solutions into the complete solution. However, we did not have independence. The aggregation did not come at the end of our puzzle doing, but rather as we went along. Thus each person's decisions directly affected the decisions of others. Somebody putting an 8 in one row might lead another to assume the spot for a 1. Somewhere, someone made an assumption based off of someone's incorrect placement of a number, creating a domino affect on the other puzzle doers and leading to our faulty solution.

Next time, if we make sure no one plays base off of a hunch (an opinion) about the placement of a number, and guarantee that no one makes a mistake in number placement, only placing numbers based on absolute certainty, we can have a better chance of solving the puzzle. Of course, assuming the perfection of each and every player is silly, so in the end there's no guarantee on the outcome of the puzzle with a group so large :)

But crowd wisdom is a real thing. Surowiecki has already given countless examples of this in the book, like the market placing correct blame on the Thiokol company a half hour after the space shuttle Challenger blew up, even though the finding of the faulty Thiokol O-rings didn't occur until days later. Or how about the collective result of the opinions of a wide variety of men on the location of the lost submarine Scorpion in 1968: they were only 220 yards off. I am far from finishing Surowiecki's book, but so far it has been an engaging read, and I look forward to gaining more insight on the wisdom of the crowd.

;U136658.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment